Dan Stewart Discusses Education Rights for Students with Disabilities

Dan Stewart served as the Legal Director of the Minnesota Disability Law Center (MDLC). Before joining MDLC, Dan practiced with a private law firm and with the state Department of Education. He also founded the University of Minnesota Law School’s Special Education clinic. In addition to being an attorney, Dan has a Master’s degree in education administration, and a PhD in social work. In this video, Dan answers questions about Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), Section 504 and behavioral supports, as well as eligibility criteria and updates to special education law. He provides outreach and training sessions to a wide variety of national, regional and local audiences.

Brown v. Board of Education

Brown consolidated five cases brought in various states across the country, challenging the exclusion of African American children from schools attended by white children in the same district. The school districts defended these practices by reference to the “separate but equal” standard, announced by the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), in upholding “whites-only” railroad cars. In Brown, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned Plessy, holding that segregating children by race in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote:

We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal…[1]

This decision provided the constitutional foundation for parents of children with disabilities and disability rights activists to press for equal educational opportunities for all children, including those with developmental and other disabilities.

Extending Brown to Children with Disabilities

In both landmark cases, the Courts interpreted the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to give parents specific rights, struck down local laws that excluded children with disabilities from schools and established that children with disabilities have the right to a public education.

P.A.R.C. v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 334 F. Supp. 279 (E.D. PA 1972)

In 1954, early in his tenure as Executive Director of the then-named National Association for Retarded Children, Dr. Gunnar Dybwad called attention to the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. He suggested that the case had enormous possibilities for children with disabilities as well. [ADA Legacy Project]

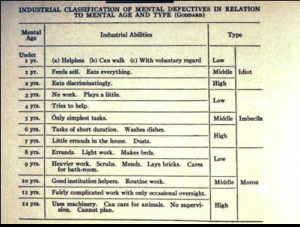

In 1971, Thomas K. Gilhool, the attorney who represented the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (P.A.R.C.), relied on Brown in his class action suit filed on behalf of 14 children with developmental disabilities who had been denied access to public education in Pennsylvania, under a state law that specifically allowed schools to exclude children who had not reached a “mental age of five years” by the time they should be enrolling in first grade. The plaintiffs argued that this exclusion violated their rights under both the Equal Protection clause and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In connection with a Consent Agreement approved by the Court a three-judge panel of the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, the Court enjoined Pennsylvania from denying any child up to age 21 admission to a public school program “appropriate to his learning capacities”, or from having his educational status changed without first being notified of and given the opportunity for a due process hearing.

The Consent Agreement stated:

Expert testimony in this action indicates that all mentally retarded persons are capable of benefiting from a program of education and training… It is the Commonwealth’s obligation to place each mentally retarded child in a free, public program of education and training appropriate to the child’s capacity.[2]

It also said:

Placement in a regular school is preferable to placement in a special school class is preferable to placement in any other type of program of education and training.[3]

Mills v. Board of Education, 348 F. Supp. 866 (D.D.C. 1972)

Mills expanded the impact of the P.A.R.C. case beyond children with developmental disabilities. The Mills class action lawsuit was brought in 1972, the same year as the P.A.R.C. case, on behalf of seven school-age children who had been denied placement in a public educational program for substantial periods of time because of alleged mental, behavioral, physical or emotional disabilities. The plaintiffs sought an injunction on the grounds that they had been denied their constitutional right to Due Process.

The District of Columbia government and school system conceded that it had the legal “duty to provide a publicly supported education to each resident of the District of Columbia who is capable of benefiting from such instruction”[4] but argued that it was impossible to do so because they lacked the necessary financial resources. The Court held that no child could be denied a public education because of “mental, behavioral, physical or emotional handicaps or deficiencies.” The Court further noted that defendants’ failure to provide such an education could not be excused by the claim of insufficient funds, stating:

If sufficient funds are not available to finance all of the services and programs that are needed and desirable in the system, then the available funds must be expended equitably in such a manner that no child is entirely excluded from a publicly supported education consistent with his needs and ability to benefit therefrom. The inadequacies of the District of Columbia Public School System, whether occasioned by insufficient funding or administrative inefficiency, certainly cannot be permitted to bear more heavily on the “exceptional” or handicapped child than on the normal child.[5]

Subsequent developments in Special Education Law

Twenty-seven federal court cases followed the P.A.R.C. and Mills decisions, leading to the pressure of federal laws guaranteeing a public education for all children. In 1975, the Education for all Handicapped Children Act, now called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), codified the right to a free, appropriate public education for all students, including those with severe disabilities. IDEA requires all public schools accepting federal funds to provide equal access to education to children with physical and mental disabilities. It also requires that each child have an “individualized education program” (IEP) that is implemented in the “least restrictive environment” possible. However, the meaning of “appropriate” education is an ongoing source of controversy and litigation. Under IDEA, states are required to develop plans with the following components:

- Provision of “full education opportunities” to all;

- Due process safeguards to aid parents in challenging many decisions regarding the education of their children;

- A guarantee that children with disabilities will be educated to the fullest extent possible;

- Procedures to assure that tests and other materials used to evaluate a child’s special needs are not culturally or racially biased; and

- Evaluation of all of the state’s children with special needs.

From the Georgia Advocacy Office, The Center for Public Representation, The Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, The Arc, DLA Piper LLP, and The Goodmark Firm, October 11, 2017

Parents and Advocates Sue State of Georgia Over Separate and Unequal Education for Thousands of Students with Disabilities

In July 2015, the United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, completed a multi-year investigation of the Georgia Network for Educational and Therapeutic Support (GNETS). The GNETS Program dates back to 1976. The investigation found “systemic unnecessary reliance on the segregated GNETS Program across the State of Georgia….” Both in terms of operation and administration of the GNETS Program, Georgia was found to be in violation of Title II of the ADA – unnecessary segregation, unnecessary reliance on segregated settings for students with behavioral disabilities, and inequality of educational opportunities for students with disabilities. The Department concluded that relevant policies, practices, and services could be modified, and the majority of students could receive services in more integrated settings.

Georgia-GNETS-students-BED-7-2015-DOJ-Letter

The investigation culminated in a class action lawsuit, filed in US District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, alleging discrimination against “thousands of public school students with disabilities by providing them with a separate and unequal education” and diverting them to the GNETS Program. The extent of the conditions found in the GNETS Program is presented in a summary of the Complaint. While the GNETS Program was originally intended to be a “placement of last resort,” it has become a “dumping ground” for students that local school districts don’t want to have to serve.

GeorgiaNETS-Complaint-Summary_-FINAL-10-10-17

Georgia-NETS-ClassAction-Press-Release-10-10-17

In the Supreme Court of the United States

Stacy Fry, Et Vir, As Next Friends of Minor E.F., Petitioners v. Napoleon Community Schools, Et Al, 580 U.S. ____(2017)

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

The scope of the exhaustion requirement under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is at issue here. The Court held that “… exhaustion is not necessary when the gravamen of the plaintiff’s suit is something other than the denial of the IDEA’s core guarantee – what the Act calls a “free and appropriate public education.”

The Court discussed at length both portions of IDEA’s exhaustion requirement, §1415(l) and the reach of that requirement. In this case, a five year old kindergarten student, enrolled at Ezra Eby Elementary School, had a trained service dog as recommended by her pediatrician. The School refused the parents’ request to have the service dog with their daughter in the classroom. The parents ultimately removed her from school and began homeschooling.

They then filed a complaint with the US Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) charging that the school’s exclusion of their daughter’s service dog violated her rights under Title II of the ADA and §504 of the Rehabilitation Act. The OCR found the school in violation; the school eventually relented. The parents, concerned about their daughter’s return to Ezr Eby, found a different public school in a different district where their daughter was well received with her service dog. The then filed suit in Federal District Court.

The District Court granted the school district’s motion to dismiss on the basis that the exhaustion requirement had not been met. The Sixth Circuit affirmed. The US Supreme Court granted cert and vacated the Sixth Circuit’s decision.

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/16pdf/15-497_p8k0.pdf

Endrew R., a Minor, By and Through His Parents and Next Friends, Joseph F. and Jennifer F., Petitioner v. Douglas County School

District Re-1

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (580 U.S. ____(2017), March 22, 2017

Thirty-five years ago, in Board of Dd. of Hendrick Hudson Central School Dist., Westchester Cty. V. Rowley . 458 U.S. 176 (1982), the United States Supreme Court established a substantive right to a “free and appropriate public education “ for certain children with disabilities but declined to create a single standard for determining when children with disabilities are receiving sufficient educational benefits to satisfy IDEA requirements.

That Court rejected an “equal opportunity standard,” because FAPE was too complex and considered such a standard as “entirely unworkable,” requiring “impossible measurements and comparisons” that a Court could not make.

The Court today has revisited the Rowley decision, vacated the judgment of the Tenth Circuit, and remanded the case for further proceedings consistent with its holding. The Administrative Law Judge and both lower courts rested on and continued to abide by the language in Rowley that instruction and services for children wth disabilities must confer “some” educational benefit so children make “some” progress, and the IEP is adequate if the benefit is “merely …more than de minimus.”

The Court clearly departs from Rowley –

“[W]e find little significance in the [Rowley] Court’s language concerning the requirement that States provide instruction calculated to ‘confer some educational benefit’…and the statement that the Act did not ‘guarantee any particular level of education’ simply reflects the unobjectional proposition that the IDEA cannot and does not promise ‘any particular [educational] outcome… No law could do that – for any child.

A child’s educational program should be ‘appropriately ambitious’ just as advancement from grade to grade is considered appropriately ambitious for children with out disabilities…The IDEA demands more.”

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/16pdf/15-827_0pm1.pdf

Special Education Resources and References

Videos and Multimedia Resources

Parallels in Time: A Place to Learn

Partners in Education Online Curriculum

How the PARC Case Began: Video Interview with Gunnar Dybwad

The Right to Education: Video Interview with Gunnar Dybwad

The Role of the Courts: Video Interview with Gunnar Dybwad

The PARC Case: Audio presentation by Tom Gilhool, Lead Plaintiff Attorney

Articles and Other Secondary Sources

ADA Legacy Project: The Right to Education Based on Brown v. Board of Education

“Access to Justice: The Impact of Federal Courts on Disability Rights.” The Federal Lawyer, December 2012.

Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Citizens (PARC) v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

United States Courts: History of Brown v. Board of Education

Legal Resources and References

PARC Cases

Opinions:

District Court (1971): 334 F.Supp. 1257

District Court (1972): 343 F.Supp. 279 (1972)

- ^BROWN et al. v.BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE COUNTY, KAN., et al., 74 S.Ct. 686, 692 (1955)

- ^Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 334 F.Supp. 1257, 1259 (E.D. Pa 1971).

- ^Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 343 F.Supp. 279, 307 (E.D. Pa 1972).

- ^Mills v. Board of Education, 348 F.Supp. 866, 871 (DC Dist. of Columbia 1972)

- ^Id. at p. 876