New York State Association for Retarded Children v. Carey

A watershed case in the evolution of the legal rights of people with disabilities to live in dignity arose out of public awareness of the horrific conditions under which children and adults with disabilities were living at the Willowbrook State Developmental Center in New York. This case set important precedents for the humane and ethical treatment of people with developmental disabilities living in institutions. This, in turn, served as the impetus for accelerating the pace of community placements for people with developmental disabilities, expanding community services, increasing the quality and availability of day programs, and establishing the right of children with disabilities to a public education.

Inhumane Conditions at Willowbrook

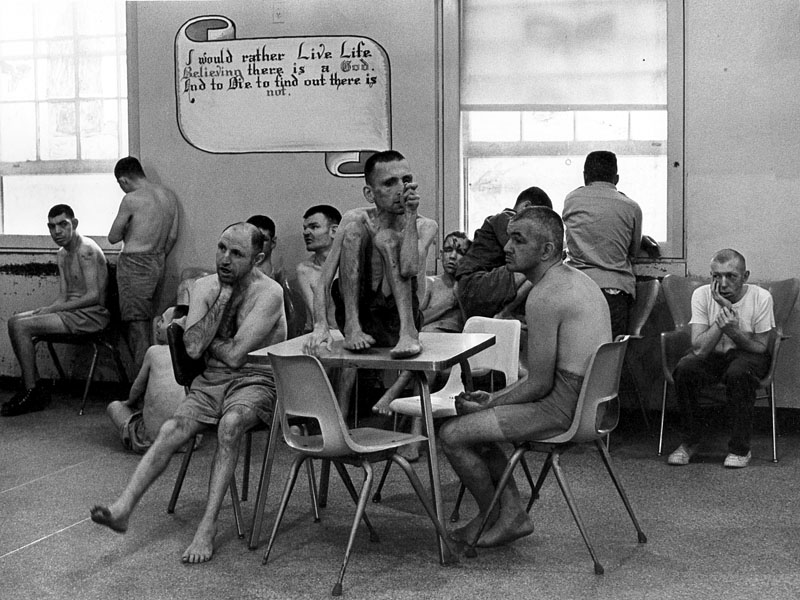

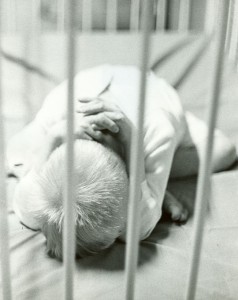

Willowbrook was a complex of buildings on Staten Island housing children and adults with developmental disabilities. At its highest population, in 1969, 6,200 residents were living in buildings meant to house 4,000. Understaffed, overcrowded and underfunded, Willowbrook was little more than a “human warehouse,” according to William Bronston, a physician at Willowbrook. The institution’s overcrowding fostered abuse, dehumanization, and a public health crisis. Hepatitis was so rampant that several researchers took advantage of the situation to use residents as participants in a controversial medical study in which residents were intentionally exposed to the deadly virus, without their consent, in order to test the effectiveness of various vaccines.

In 1965, Senator Robert Kennedy paid an unannounced visit to Willowbrook. He found thousands of residents “living in filth and dirt, their clothing in rags, in rooms less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo.” Kennedy went on to describe the institution as a “snake pit.”[1] The visit put conditions at Willowbrook into the national spotlight and the state of New York responded by developing a five-year improvement plan. However, after making minor adjustments, conditions at the institution quickly reverted to the inhumane conditions that had thrust it into public consciousness.

In 1972, ABC News investigative reporter Geraldo Rivera again drew national attention to Willowbrook with a television exposé that was watched by millions. Willowbrook: The Last Disgrace, exposed the institution’s serious overcrowding, dehumanizing practices, dangerous conditions and regular abuse of residents. The public was again outraged. However, this time, the outrage served to spur parent advocacy groups to take action in federal court.

The Willowbrook Lawsuit

Following the Rivera exposé, parents of Willowbrook residents filed a class action suit in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York on March 17, 1972. The lawsuit alleged that conditions at Willowbrook violated the constitutional rights of the residents. Parents outlined multiple violations, including:

- Confining residents for indefinite periods;

- Failing to release residents eligible for release;

- Failing to conduct periodic evaluations of residents to assess progress and refine goals and programming;

- Failing to provide habilitation for residents;

- Not providing adequate educational programs, or services such as speech, occupational, or physical therapy;

- Overcrowding;

- Lack of privacy;

- Failure to provide protection from theft of personal property, assault, or injury;

- Inadequate clothing, meals, and facilities, including toilet facilities;

- Confining residents to beds or chairs, or to solitude;

- Lack of compensation for work performed;

- Inadequate medical facilities; and

- Understaffing and incompetence in professional staff.

The lawsuit sought immediate injunctive relief to improve conditions at Willowbrook, including hiring more staff, providing adequate medical care, prohibiting the use of seclusion and improper physical and chemical restraints, and providing adequate and appropriate clothing and physical conditions for residents. The plaintiffs alleged that the existing conditions violated the residents’ constitutional right to treatment under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and that their denial of a public education violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In April 1973, U.S. District Court Judge Orrin G. Judd rejected the plaintiffs’ arguments that the Due Process Clause guaranteed a right to treatment and that the denial of public education violated the Equal Protection Clause. However, he did find that the conditions in Willowbrook violated the constitutional right of persons living in state custodial institutions to be protected from harm. According to Judge Judd, the plaintiffs’ constitutional right to protection from harm in a state institution meant that the residents of Willowbrook were “entitled to at least the same living conditions as prisoners.”[2] This right, he continued, “may rest on the Eight Amendment, the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (based on irrational discrimination between prisoners and innocent mentally retarded persons).”[3] Accordingly, Judge Judd granted much of the requested injunctive relief, including prohibiting the use of seclusions and restraints, increasing medical, therapeutic and recreational staffing, requiring maintenance, and requiring regular progress reports.

With this injunctive order in place, the case proceeded to trial on October 1, 1974, with the parties continuing negotiations for months afterwards. The case was settled on April 30, 1975, when Judge Judd signed the Willowbrook Consent Judgment: New York State Association For Retarded Children, Inc., et al., v. Hugh L. Carey, 393 F. Supp. 715 (1975).

The Willowbrook Consent Judgment

The Willowbrook Consent Judgment set forth guidelines and requirements for operating the institution and established new standards of care for all Willowbrook residents at the time of the settlement. These standards of care were “not optimal or ideal standards, nor… just custodial standards.” They were based on the recognition that people with developmental disabilities, “regardless of the degree of handicapping conditions, are capable of physical, intellectual, emotional and social growth, and upon the further recognition that a certain level of affirmative intervention and programming is necessary if that capacity for growth and development is to be preserved, and regression prevented.”[4]

The Consent Judgment outlined specific procedures and instructions for treatment of residents, covering issues such as resident living, the environment, programming and evaluation, hiring of personnel, education, recreation, food and nutrition, dental and medical care, therapy services, use of restraints, conditions for residents to provide labor to the facility, and conditions for research and experimental treatment.

Significantly, the Consent Judgment also declared as the primary goal of the institution and the New York Department of Mental Hygiene to “ready each resident…for life in the community at large”[5] and called for the placement of Willowbrook residents in less restrictive settings. The Consent Judgment set a goal of reducing the number of residents living at Willowbrook to no more than 250 by 1981[6] although this did not prove feasible.

Although the parties ended up in Court many more times in disputes over the ongoing implementation of the Consent Decree, it was, in a sense, fully implemented in 1987, when the Willowbrook State School and Hospital officially closed.

What Happened Next?

The political reaction to this case led to the enactment of legislation such as:

- The Protection and Advocacy (P&A) System in the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act (1975);

- The Education For All Handicapped Children Act, P.L. 94-142 (1975); and

- The Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA)(1980).

The Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act and CRIPA were the first federal civil rights laws protecting people with disabilities, leading to the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Willowbrook Resources and References

Videos and Multimedia Resources

Willowbrook Photo Essay, Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities

Timeline of the Willowbrook Lawsuit, Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities

Parallels in Time II, Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities

Willowbrook Exposé: Touring Willowbrook

Public Hostage: Public Ransom, Inside Institutional America by Dr. William Bronston

Public Hostage: Public Ransom, Inside Institutional America. Photographs by Dr. William Bronston

ADA Legacy Project: Willowbrook Leads to New Protections of Rights

Articles and Other Secondary Sources

- Complete Documentation of the Work of the Willowbrook Review Panel

- “Access to Justice: The Impact of Federal Courts on Disability Rights.” The Federal Lawyer, December 2012.

This article was originally printed in the December 2012 issue of The Federal Lawyer and is used with permission.

Opinions

District Court

Initial Injunctive Relief: New York State Association for Retarded Children v. Rockefeller, 357 F. Supp. 752 (1973)

Approval of Consent Decree: New York State Association for Retarded Children v. Carey, 393 F. Supp. 715 (1975)

Consent Decree

US Court of Appeals, Second Circuit decisions concerning implementation of Consent Decree:

- New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey, 596 F.2d 27 (1979)

- New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey, 631 F.2d 162 (1980)

- New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey, 706 F.2d 956 (1983)

- New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Carey, 711 F. 2d 1136 (1983)

References

- ^The Minnesota Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities, The ADA Legacy Project, Willowbrook Leads to New Protections of Rights, Moments in Disability History 9, 2013. Can be found at: http://mn.gov/mnddc/ada-legacy/ada-legacy-moment9.html

- ^New York State Ass’n for Retarded Children, Inc. v. Rockefeller, 357 F. Supp. 752, 764 (1975).

- ^Id

- ^New York State Association For Retarded Children, Inc., et al., v. Hugh L. Carey,. 393 F. Supp. 715 (1975) at ¶1.

- ^Id. at Appendix A, ¶ V. 9

- ^Id. at Appendix A, ¶ V.1